Saturday, 12 April 2014

Tuesday, 8 April 2014

The Ultimate Guide to Learning how to use Your first DSLR

If you consider yourself a beginner who is unsure of how to make the most of your camera, this post is designed for you. It’s intended to be a brief, a one-stop shop to help you take your camera off auto, and take control of your DSLR. It isn’t intended to be a replacement for your camera manual, so will not explain every last setting in great depth, but will cover enough of the basics to get you in control of your camera, and give you the key topics to go back to your manual to read.

The topics covered in this post are:

1. Shooting modes

- aperture priority

- shutter priority

- program

- manual

2. ISO

3. Completion of the ‘exposure triangle’

4. Metering

- exposure compensation (+/-)

5. Focussing

- focussing modes (AF-S/AF-C)

- focus points

6. File size/types

- raw vs jpeg

7. White balance

Which should be more than enough to get you on your way. So let’s begin…

1. Shooting modes

The best place to start is with shooting modes. The shooting modes will most likely be found on a dial labelled with ‘auto, Av, Tv, P, M’ and maybe more. Selecting a shooting mode will determine how your camera behaves when you press the shutter, for example, when ‘auto’ is selected, the camera will determine everything to do with the exposure, including the aperture and shutter speed. The other modes, ‘Av, Tv, P, M’, are there to give you control:

Don’t worry if your mode dial looks a little different; different manufacturers use different abbreviations for the shooting modes. Your mode dial may have the letters ‘A, S, P, M’ (instead of Av, Tv, P, M), yet they all function in the same way. Below, I have given each abbreviation for the given mode.

Aperture Priority (Av or A)Aperture priority can be thought of as a ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode. When this is selected, you as the photographer set the aperture and the camera will automatically select the shutter speed. So what is aperture and when would you want to control it?

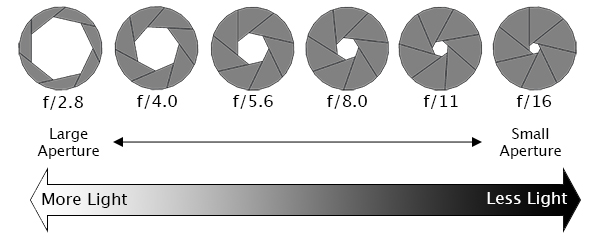

The aperture is the size of the opening in the lens through which light is allowed to pass whenever the shutter is opened – the larger the aperture, the more light passes through.

The aperture is measured in ‘f-stops’ and is usually displayed using an ‘f-number’, e.g. f/2.0, f/2.8, f/4.0, f/5.6, f/8.0 etc, which is a ratio of focal length over diameter of the opening. Therefore, a larger aperture (a wider opening) has a smaller f-number (e.g. f/2.0) and smaller aperture (a narrower opening) has a larger f-number (e.g. f/22). Reducing the aperture by one whole f-stop, e.g. f/2.0 to f2/8 or f/5.6 to f/8.0, halves the amount of light entering the camera.

Aperture is one of the most important aspects of photography as it directly influences the depth of field – that is, the amount of an image that is in focus. A large depth of field (achieved by using a small aperture (large f-number)) would mean that a large distance within the scene is in focus, such as the foreground to the background of the landscape below.

An aperture of f/13 was used here to give a large depth of field, ensuring that the whole image, from the foreground grasses to the background mountains. was sharp

Whereas a shallow depth of field (achieved by using a large aperture (small f-number)) would produce an image where only the subject is in sharp focus, but the background is soft and out of focus. This is often used when shooting portraiture or wildlife, such as the image below, to isolate the subject from the background:

A large aperture of f/4.5 was used to capture this water vole, against a soft, out of focus background

So when using aperture priority, you can get complete control over your depth of field, whilst the camera takes care of the rest.

Shutter Priority (Tv or S)Similarly to aperture priority, this is another ‘semi-automatic’ shooting mode, though in this instance, you as the photographer set the shutter speed and the camera will take care of the aperture. The shutter speed, measured in seconds (or more often fractions of a second), is the amount of time the shutter stays open when taking a photograph. The longer the shutter stays open, the more light passes through to the sensor to be captured.

You would select a short shutter speed if you wanted to freeze a fast moving subject, such as shooting sports, action or wildlife, for example:

A very fast shutter speed of 1/4000th sec was used to freeze the motion of this grouse in flight

You would use a long shutter speed if you wanted to blur a moving subject, for example water rushing over a waterfall (slower shutter speeds will require you to put the camera on a tripod to ensure the camera is held steady whilst the shutter is open):

To capture the motion of the waves, and render the water with a soft, milky texture, a shutter speed of 6 seconds was used here

So whilst you worry about what shutter speed you need for a given photograph, the camera will determine the appropriate aperture required to give the correct exposure.

Aperture and shutter priority shooting modes may be semi-automatic, meaning that some may deride their use because they’re not fully manual, however they are incredibly useful modes to shoot in that can give you enough creative control to capture scenes as you envisage them.

Program (P)Program mode is almost a halfway house between the semi automatic modes of aperture/shutter priority and full manual control. In program mode, you are able to set either the aperture or shutter speed, and the camera will maintain the correct exposure by adjusting the other one accordingly, i.e. as you change the aperture, the shutter speed will automatically change, and vice versa. This gives you additional freedom that using either aperture priority or shutter priority cannot give without switching between shooting modes.

Manual (M)Manual mode is exactly what it sounds like, you are given full control over the exposure determination, setting both the aperture and shutter speed yourself. There will be an exposure indicator either within the viewfinder or on the screen that will tell you how under/over exposed the image will be, however, you are left to change the shutter speed and aperture yourself to ensure you achieve the correct exposure.

Practically Speaking: as a first step to taking your camera off ‘auto’, aperture priority and shutter priority modes offer two very simple ways to start to understand how the different setting impact your images and are a perfect starting place for learning how to use your camera more creatively.

2. ISO

ISO is a measure of how sensitive the sensor of your camera is to light. The term originated in film photography, where film of different sensitivities could be used depending on the shooting conditions, and it is no different in digital photography. The ISO sensitivity is represented numerically from ISO 100 (low sensitivity) up to ISO 6400 (high sensitivity) and beyond, and controls the amount of light required by the sensor to achieve a given exposure

At ‘low’ sensitivities, more light is required to achieve a given exposure compared to high sensitivities where less light is required to achieve the same exposure. To understand this, let’s look at two different situations:

Low ISO numbersIf shooting outside, on a bright sunny day there is a lot of available light that will hit the sensor during an exposure, meaning that the sensor does not need to be very sensitive in order to achieve a correct exposure. Therefore, you could use a low ISO number, such as ISO 100 or 200. This will give you images of the highest quality, with very little grain (or noise).

Taken at ISO 100, the image does not show signs of noise (even when looking at the 100% crop (right)

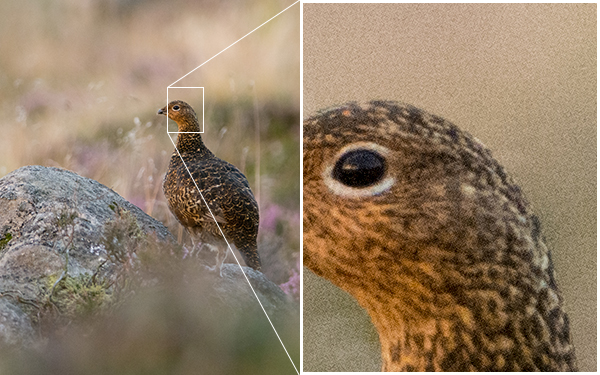

High ISO numbersIf shooting in low light conditions, such as inside a dark cathedral or museum for example, there is not much light available for your camera sensor. A high ISO number, such as ISO 3200, will increase the sensitivity of the sensor, effectively multiplying the small amount of available light to give you a correctly exposed image. This multiplication effect comes with a side effect of increased noise on the image, which looks like a fine grain, reducing the overall image quality. The noise will be most pronounced in the darker/shadow regions.

This image was taken as the sun was going down, meaning there was not much ambient light. Therefore, this was shot with ISO4000, however you can see very obvious noise in the 100% crop (right)

Practically Speaking: you want to keep the ISO as low as possible, as the lower the ISO, the less noise and the higher the quality of the resulting image. Outside on a sunny day, select ISO200 and see how it goes. If it clouds over, maybe select an ISO between 400-800. If you move indoors, consider an ISO of around 1600 or above (these are approximate starting points).

Most digital SLRs now have an ‘auto-ISO’ function, where the camera sets the ISO depending upon the amount of light in which you are shooting, keeping it as low as possible. Auto-ISO is a very useful tool when starting out with your camera, as it is allows you to define an upper limit i.e. where the images become too noisy such as ISO1600 or 3200, and then forget about it until situations where you specifically want to override the automatic setting, for example if taking landscape images using a tripod, you can afford to use the lowest ISO possible.

3. Completion of the Exposure Triangle

It’s important to note that aperture, shutter speed and ISO are all part of the ‘exposure triangle’. They all control either the amount of light entering the camera (aperture, shutter speed) or the amount of light required by the camera (ISO) for a given exposure.

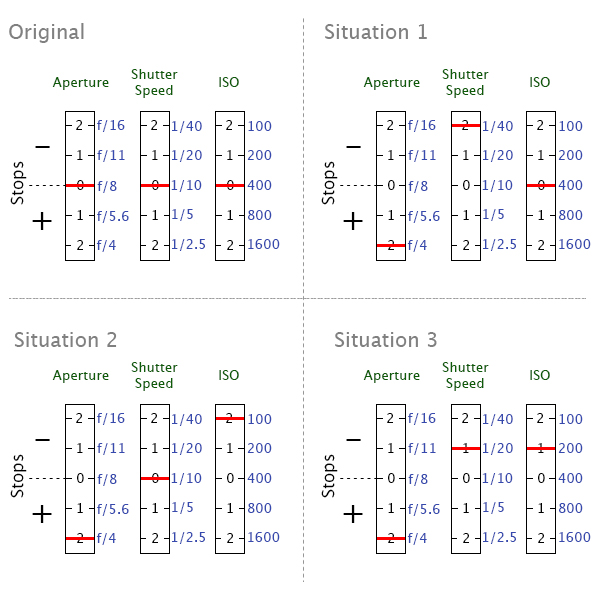

Therefore, they are all linked, and understanding the relationship between them is crucial to being able to take control of your camera. A change in one of the settings will impact the other two. For example, considering a theoretical exposure of ISO400, f/8.0, 1/10th second. If you wanted to reduce the depth of field, and decided to use an aperture of f/4.0, you would be increasing the size of the aperture by two whole f/stops, therefore increasing the amount of light entering the camera by a factor of 4 (i.e. increasing by a factor of 2, twice). Therefore, to balance the exposure, you could do the following:

- Situation 1: Reduce the shutter speed by a factor of 4, i.e. to 1/40th second.

- Situation 2: Reduce the ISO by a factor of 4, i.e. to ISO100

- Situation 3: A combination of the above, shutter speed by a factor of 2 (to 1/20th second) AND reduce the ISO bv a factor of 2 (to ISO200).

Aperture, shutter speed and ISO are all facotrs that influence your exposure, and are all linked. It’s just a case of balancing the books!

They all have the net effect of reducing the amount of light by a factor of 4, countering the change in aperture. It’s just a case of understanding that they are all linked, and so changing one setting, will cause a change in another.

Using a combination of the semi-automatic shooting modes and auto-ISO would mean you won’t necessarily need to think about adjusting your exposure in such a way initially, however understanding the relationship that ISO or aperture has with shutter speed, and knowing the practical implications is a big step in mastering your DSLR .

4. Metering

Through out all of the above discussion, I have said that the camera calculates the exposure depending on the amount of available light, but what is it actually doing?

When taking a photograph, using any form of automatic exposure calculation (e.g. aperture priority mode, shutter priority mode, auto-ISO etc) the camera always tries to calculate an ‘average’ exposure. It will asses the entire scene, both light and dark areas, and determine the exposure so that all of the tones within the entire image average to 18% grey – called the ‘middle’ grey.

This is known as metering, and it is the reason that if you point your camera at a bright white scene, such as after it has snowed, and take a photograph the resulting image will always appear darker than you or I see it. Similarly, if you point your camera at a really dark scene, such as a low-lit room, and take a photograph the resulting image will always be brighter than you or I see it.

The scene is always being averaged by the camera and most of the time that results in the image appearing to be correctly exposed. However, you can control what areas of the scene are being assessed by the camera in order to influence the way in which the exposure is metered.

Generally, there are three metering modes that you can choose from:

Average - The camera will assess the tones across the entire image form corner to corner, and expose the scene to 18% grey from that assessment.

Centre-weighted – The camera weights the exposure reading for the area in the centre of the viewfinder that can total up to approximately 80% of the scene, ignoring the extreme corners of the image.

Spot metering – The camera will use a very small area of the scene, typically a small circle in the centre of the viewfinder that totals approximately 5% of the viewfinder area. It will make the assessment of dark/light tones in this area and expose the entire scene to 18% grey, from that assessment.

Practically speaking: when starting out with your camera, either average or centre weighted metering are a good starting point. They will both provide a fairly consistent measure of the exposure required and, if you select one mode and stick with it, you will soon begin to understand when a scene will be under exposed (i.e. too dark) or over exposed (i.e. to light) compared to how you see it with your own eyes.

But what can you do if a scene is under/over exposed? That is where exposure compensation comes in.

Exposure compensation

Generally found on a small +/- button near the shutter, this is one of the most useful functions to learn how to use. It allows you to either increase or decrease the cameras default meter reading to account for the actual brightness of a scene.

If a scene contains primarily bright tones and is being rendered too dark, for example, a bright white snow scene (that will typically be reduced to 18% grey by the default metering system), you can apply positive exposure compensation to let the camera know that the scene should be lighter than middle grey.

A spring lamb leaping in front of a snowy hillside. Left: Straight out of camera, with the snow caught as grey. Right: With +2 stops exposure compensation (added in post processing). The bright snowy background caused my camera to underexpose this scene by nearly two stops, which could have been corrected by exposure compensation in camera.

Conversely, if a scene contains primarily dark tones and is being rendered too light, for example, a dark night scene (that will typically be increased to 18% grey by the default metering system), you can apply negative exposure compensation to let the camera know that the scene should be darker than middle grey.

5. Focussing

Regardless of what shooting mode you are using, or what ISO you define, the chances are there will be a subject of your image that you want to have in focus. If that focus is not achieved, the image will not be what you wanted.

Autofocus modesDSLRs come with a range of autofocus modes, however, for simplicity, the two that are most important to understand are AF-S and AF-C

AF-S – autofocus-single. This is best used when taking photos of stationary subjects such as portraits of people, landscapes, buildings etc. When you half-press the shutter, the focus will be acquired and locked on that point for as long as you hold the button down. If you want to change to focus, you need to release the button, recompose and then re-half-press.

AF-C – autofocus-continuous. This is best used when taking photos of action or moving subjects such as sports and wildlife. When you half-press the shutter, focus will be acquired and locked on to a given subject. When that subject moves, the focus will adjust with it, refocusing all of the time until the photograph is taken.

(These modes are not to be confused with the AF/MF switches on the lens, where AF stands for autofocus and MF stands for manual focus. That switch is an override for if you want to manually focus your lens. If you want to make use of the autofocus modes discussed above, ensure the lens is set to AF).

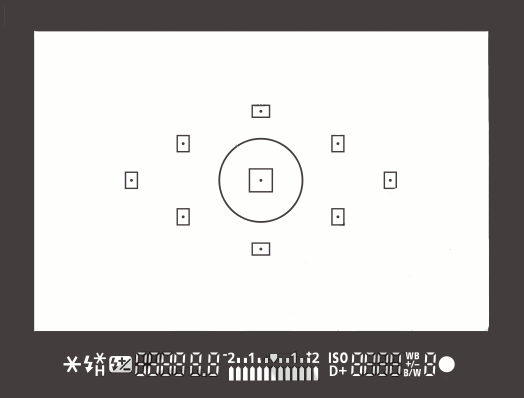

Focus PointsBoth of those focus modes rely on what are known as focus points. When you look through the viewfinder, you should see a number of squares/dots overlaid across the screen. When you half-press the shutter, you should see one of these squares be highlighted in red. That is the active focus point, and it is that position within the frame that the camera is focussing on. A viewfinder with 9 focus points is shown below:

New DSLRs can come with over 50 focus points and the temptation is to leave it on fully automatic focus point selection, with the thinking that the camera will be able to select the correct focus point. However, only you know what you want to focus on, and there is no better way than ensuring the correct subject is in focus than by using one focus point, and placing that focus point over the subject.

If you select a single focus point, you should be able to change which point is active fairly easily either by using directional buttons one of the dials. If you select a focus point that is on your desired subject, you will ensure that the camera focuses where you want it to. After a small amount of practice, you will soon get into the habit of being able to change the focus point without taking the camera away form your eye.

Practically speaking: Initially, set your camera to use a single focus point (your camera manual should tell you how to do this). This way, you will be able to choose what you are focussing on, ensuring that the subject you want to capture is in focus. Once you are familiar with the basic focussing modes and focus point selection, you can then explore the more advanced modes that your camera may offer.

6. File Size/Types

You will have the option to be able to change the size of the images that your camera records, and in which file type. You want to set the file size to the largest possible (whether it is ‘large’ or ‘fine’ or ‘super fine’) to ensure that you are making the most of the mega pixels that you have just invested in.

You will also have the option of choosing whether to record the images as ‘raw’ or ‘jpeg’ file type. A raw file is uncompressed, and so contains a lot of image data that allows for a lot of flexibility during post-processing (i.e. on your computer) but also comes with additional complications such as the need to ‘process’ every file using dedicated editing software and a larger file size. A jpeg is a compressed file type, that is automatically processed by the camera. They will be ‘print ready’ straight out of the camera, and are much smaller files, meaning you can fit more images per memory card.

Practically speaking: When starting out with your camera, using jpeg is the most straight forward. It will enable you to get the best results whilst you learn the basics or your camera before complicating matters with post-processing of raw files.

7. White Balance

If shooting in jpeg, as recommended above, you will need to make sure you set your white balance before taking a picture. The white balance can significantly impact colour tone of your photographs. You may have noticed that sometimes your images have a blueish tone to them or, in others, everything looks very orange. This is to do with the white balance and, whilst you can make some adjustments to the image on your computer, it is much simpler if you get it right up-front.

Different light sources (such as the sun, light bulbs, fluorescent strips etc) emit light of different wavelengths, and therefore colours, which can be described by what is known as colour temperature. Light from a candle, or from the sun during sunrise/sunset, is very warm, and contains a lot of red/orange wavelengths; whereas light from a fluorescent strip is much cooler, containing a lot of blue wavelengths. This coloured light is reflected off of surfaces, but our brain in clever enough to recognise this and automatically counter the effect, meaning that we still see a white surface as a white surface. However, your camera is not that intelligent, and unless told otherwise, will record the orange or blue tones giving the colour cast to your images.

Left: The image captured using auto white balance has a heavy yellow tone from the artificial street lighting. Right: the same image, corrected for a ‘Tungsten’ white balance, giving the cooler tones on the stone work, and the bluer sky

As the colour temperature of different light sources is well known, there are a number of presets built into your camera that help to overcome the different colours of light in different situations – cooling the warm light, and warming the cool light – all in the cause of trying to capture the colours of the scene accurately. The ‘auto’ feature (auto WB or AWB) will attempt to predict the colour of the light by detecting the predominant colour of the scene and then countering it, however it may not necessarily make a correct decision, leaving you with inaccurate colours. Therefore it is best to set the colour balance before you take your image and just to make sure (note: the above image was a raw file giving me a lot of latitude for white balance correction. Jpeg files are not as susceptible to white balance adjustments, meaning the white balance correction needs to be made before the image is taken):

Daylight – To be used on clear sunny days. Bright sunlight, on a clear day is as near to neutral light that we generally get

Cloudy – To be used when shooting on a cloudy day. Adds warm tones to daylight images.

Shade – To be used if shooting in the shade, as shaded areas generally produce cooler, bluer images, so need warming up.

Tungsten – Used for shooting indoors, under incandescent light bulbs, or under street lights, to cool down the yellow tones.

Fluorescent – Compensates for the green/blue tones of fluorescent light strips when shooting indoors.

Flash – the flash will add a cool blue cast to the image, so used to add some warmth.

Friday, 4 April 2014

COMPACT VS. DIGITAL SLR CAMERAS

Choosing between a compact (or "point and shoot") and a digital SLR camera is often the first big purchasing decision when starting out with photography. Not only is it potentially a big financial decision, but it may also determine what kinds of shots you'll be capable of capturing. This tutorial cuts through all the marketing hype in order to highlight only the most important differences between each camera type — thereby helping you to decide which one is best for you and your shooting style.

Ultra-Wide Angle of View

Ultra-Wide Angle of View

Shallow Depth of Field

Shallow Depth of Field

Compact Camera Pixels

Compact Camera Pixels

SLR Camera Pixels

SLR Camera Pixels

Large Dynamic Range Example

Large Dynamic Range Example

High ISO Speed Example

High ISO Speed Example

OTHER COMMON DIFFERENCESThe key here is that a different sensor size is just a trade-off; one size isn't necessarily all-around better than another, so you need to consider how the pros/cons of each will fit into your intended shooting style.

|  | |

| Compact Camera | SLR Camera |

OVERVIEW

What exactly does it mean for a camera to be a compact (or point and shoot) versus an SLR? Strictly speaking, SLR cameras just have viewfinders that see the same light as the camera's sensor (more on this later), but in practice this isn't the only distinction. While the line between each continues to blur, these three differences usually* still apply:

- Viewfinder Mechanism

- Fixed vs. Interchangeable Lenses

- Camera Sensor Size

There's also a range of more minor differences (which vary depending on the camera brand or model), the above three are often what most impact one's photography. The next several sections will focus on what these three differences actually mean in practice, and how your photography style will be impacted. At the end, we'll also discuss some of the other more minor differences between the two camera types.

*Notable Exceptions: The "Micro Four Thirds" or 4/3 standard has interchangeable lenses, but doesn't use the standard SLR viewfinder mechanism (Olympus/Panasonic cameras). Some budget SLR cameras may also have fixed lenses, and some high-end compact style cameras can have sensors that are nearly as large as an SLR — but each is the exception rather than the rule.

However, this deserves mentioning up-front: SLR cameras are usually MUCH more expensive than compact cameras — mostly as a consequence of the above three differences (we'll discuss why later). Also, unlike with compact cameras, purchasing an SLR camera is only part of the cost; you may have to buy additional lenses, an external flash and other accessories. These can even end up costing more than the camera itself.

1. VIEWFINDER MECHANISM

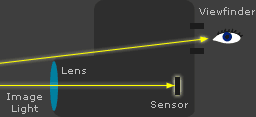

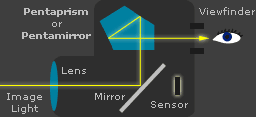

Unlike compact cameras, with an SLR camera what you're seeing through the viewfinder is the same light that will reach your camera's sensor when you press the shutter button:

|  | |||

| Compact Camera | SLR Camera: | Mirror Down | Mirror Up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

With an SLR, when you press the shutter button, the mirror flips up and the light that was formerly being re-routed to your eye instead gets sent straight to the camera sensor. Move your mouse over the buttons above to see how this works. The flipping up of the mirror is also what makes the characteristic clicking or snapping sound that we've come to associate with SLR cameras.

With a compact camera, the viewfinder mechanism instead just tries to estimate what light will reach the sensor, so it's potentially less accurate. Compact cameras may also use what's called an electronic viewfinder (EVF), which attempts to re-create what an SLR viewfinder would see — but by instead using the electronic image from the sensor.

Note: The above behavior is in fact why they're called "Single Lens Reflex" (SLR) cameras — because the same lens is used to produce the image in the viewfinder as is used to capture that image at the sensor, and the mirror reflects light to the viewfinder ("reflex" referred to the reflection in German). However, this terminology can be a little confusing, because SLR cameras are the type of camera that can use more than just a "single lens" — not compact cameras.

The need for a prism/mirror is one of the reasons why SLR cameras cost more (other than sensor size), and can make a big difference for a camera designer/manufacturer. However, in practice the sensor size and ability to change lenses will likely make more of a difference to your photography. This is especially true since many camera owners choose to use the rear LCD screen instead of the viewfinder.

On the other hand, if your work requires seeing exactly the light that will be captured, then you should certainly opt for an SLR. Otherwise, you can usually still see exactly how that light will be captured using either a compact or an SLR camera — by looking at the rear LCD in "live view" mode, and by using a live histogram.

2. FIXED vs. INTERCHANGEABLE LENSES

The fact that SLR cameras can change out their lenses is likely the first difference that one notices, or knows ahead of time. Yes, many compact cameras can use lens adaptors (especially the high-end variety), but the original lens still remains on the camera.

Why would a camera need more than one lens? It is difficult if not impossible to design a single lens that can capture scenes using the wide range of styles commonly used by photographers — all without noticeably sacrificing quality and portability. Each style is therefore far better suited by a single, special purpose lens.

In practice, being able to use different lenses usually means that:

- You'll be able to use wider lens apertures (lower f/stops), which will enable a shallower depth of field and/or better low-light performance.

- You'll be able to use specialized lenses, such as ultra-wide angle lenses, fish-eye lenses and extreme telephoto lenses, which will give you more creative options.

- You'll have the potential to achieve better image quality, primarily because your lens will likely have been more specifically designed for the task at hand.

For example, with portraits one could use a wide aperture (such as f/2.0 or less) in order to create a smooth out of focus background and isolate their subject. Alternatively, with architecture one could use an ultra-wide angle lens that's been designed to also minimize distortion (causing otherwise straight lines to appear curved). Neither of these scenarios would be possible with the vast majority of compact cameras.

Ultra-Wide Angle of View

Ultra-Wide Angle of View Shallow Depth of Field

Shallow Depth of Field

photo on left courtesy of eliya

However, using more than one lens also means that:

- You need to carry more lenses with you if you plan on shooting a range of different styles and subjects. This decreases the portability of your camera system.

- You need to change lenses every time you wish to change shooting styles. This can interrupt your shooting rhythm.

- You might introduce dust onto your camera's sensor each time you have to change lenses. This can reduce image quality and be difficult to remove.

Of course, to negate any potential inconvenience, you could always choose your favorite all-around lens for your SLR and just stick with that. In addition, the built-in lens on a high-end compact camera can sometimes produce higher quality images than a stock or budget SLR lens, and is often also a lot more versatile. However, once you start spending a lot more, compact camera lenses rarely hold their own against high-end SLR lenses.

3. CAMERA SENSOR SIZE

In general, compact cameras have much smaller camera sensors than SLR cameras. This is a less commonly known "under the hood" difference between SLR and compact cameras, but is likely one that will make the most noticeable impact on image quality.

What does this mean in practice?

- Cost. Larger sensors are much more expensive to make, and usually require correspondingly more expensive lenses. This is the biggest reason why SLR cameras cost so much more than compact cameras.

- Weight & Size. Larger sensors require much heavier and larger camera lenses and camera bodies, because the lens needs to capture and project light over a larger sensor area. Other than reducing portability, this can also be a disadvantage because it makes one look more conspicuous with their large SLR camera/lens (thereby making candid people shots more difficult).

- Depth of Field. Larger sensors create a shallower depth of field at the same aperture setting. For example, a lens at f/4.0 on a compact camera likely won't create a blurred background in a portrait, whereas f/4.0 on an SLR camera will likely create a smooth, creamy background (depending on subject distance). This can be an advantage for portraits, but a disadvantage for landscapes.

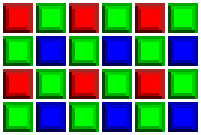

- Image Noise. For the same number of megapixels, larger sensors have much larger photosites/pixels* (as shown above). This increased light-gathering area means that these pixels will be more sensitive to tiny amounts of light — resulting in less image noise. This means that an SLR camera can usually get away with a much higher ISO setting than a compact camera without appearing noisier.

- Dynamic Range. Another consequence of having physically larger pixels is that SLR cameras can usually capture a greater range of light to dark without having this become solid white or black, respectively (a higher "dynamic range"). This reduces the chance of blown highlights in the sky or other bright objects, and can preserve more details in the deep shadows.

Large Dynamic Range Example

Large Dynamic Range Example High ISO Speed Example

High ISO Speed ExampleOTHER COMMON DIFFERENCESThe key here is that a different sensor size is just a trade-off; one size isn't necessarily all-around better than another, so you need to consider how the pros/cons of each will fit into your intended shooting style.

In addition to what's already been discussed, each camera type may also have other advantages, depending on the specific brand or model. These include:

Compact Camera Advantages

- Live view rear LCD (although most newer SLR's have this feature)

- Greater range of pre-programmed creative modes

- No mirror/shutter mechanism that can fail after ~10-100K shots

SLR Camera Advantages

- Faster camera autofocus

- Much less shutter lag (delay between pressing the shutter and starting the exposure)

- Higher maximum frame rate

- RAW file format support (although most high-end compact cameras have this)

- Ability to take exposures longer than 15-30 seconds (using manual or bulb mode)

- Offers complete manual exposure control

- Ability to use an external flash unit (but many high-end compact cameras have this)

- Manual zoom control (by twisting the lens as opposed to using an electronic button)

- Greater range of ISO speed settings

- Ability to upgrade just the camera body and keep all of one's lenses

However, many of the above differences follow from the fact that one often spends a lot more on an SLR than a compact camera, and aren't necessarily inherent to each type. If one spends enough on a prosumer/high-end compact camera, they can often attain many of the above features typically found with SLR cameras.

SUMMARY: COMPACT vs. DIGITAL SLR

The preference between each camera type really comes down to one of (a) flexibility and the potential for higher image quality versus (b) portability and simplicity. This choice often isn't a matter of which is right for a given person, but which is better for a given shooting environment and intended photo use.

Compact cameras are much smaller, lighter, less expensive and less conspicuous, but SLR cameras allow for a shallower depth of field, a greater range of subject styles and the potential for higher image quality. Compact cameras are probably better for learning photography, since they cost less, simplify the shooting process and are a good all-around option for capturing many types of scenes out of the box. SLR cameras are much better suited to specific applications, and when size and weight aren't important.

Costs aside, many prefer to own both types of cameras. That way they can take their compact camera to parties and long hikes, but have an SLR available when they need to capture indoor subjects in low-light, or when they're going somewhere specifically for photography (such as for landscapes or events).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)